Undergraduate researcher Conner Verhulst unearths a fondness for an unusual creature.

Conner Verhulst knew veterinary medicine wasn’t for him, even before kennel-cleaning duty.

It wasn’t that he didn’t love animals — quite the contrary. As an attendant in a Kansas City clinic, his tasks also included assisting with trauma surgery and holding pets during euthanasia injections. But the experiences, though invaluable, always reinforced his true aspirations to work with humans.

“Many of the things I saw were similar ailments and diseases you’ll see in people,” says Verhulst, a senior biology major from Kansas City. “The anatomy of it piqued my interest. I’m very into anatomy now, and I attribute that to my desire to go into medicine.”

Enter Casey Holliday, MU associate professor of pathology and anatomical sciences. Holliday’s lab studies the organ systems of vertebrates to discover how they help the creatures adapt to their environment. One object of his attention is the pangolin, an odd and endangered animal in southeast Asia and southern Africa hunted for its scales which in some cultures are thought to have medicinal properties.

Think of an aardvark crossed with an armadillo, only cuter.

“They eat ants and have tube-like faces with long, sticky tongues that shoot out of their mouths,” says Holliday, an expert in the cranial function of lizards, crocodiles and birds. “We don’t really know a lot about the anatomy of pangolins. Conner had natural skills of carpentry and engineering, so it seemed like a fun project he could help lead as an undergrad.”

Holliday had obtained a partial pangolin skeleton serendipitously, after his presentation on imaging exotic species at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine’s Show-Me Exotics Symposium. It was there that he met Copper Aitken-Palmer, a veterinarian and pangolin specialist from the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago. Palmer explained the challenges of intubating — and therefore breeding in captivity — pangolins, whose tongues retract down their throats into the abdomen and culminate near the right kidney.

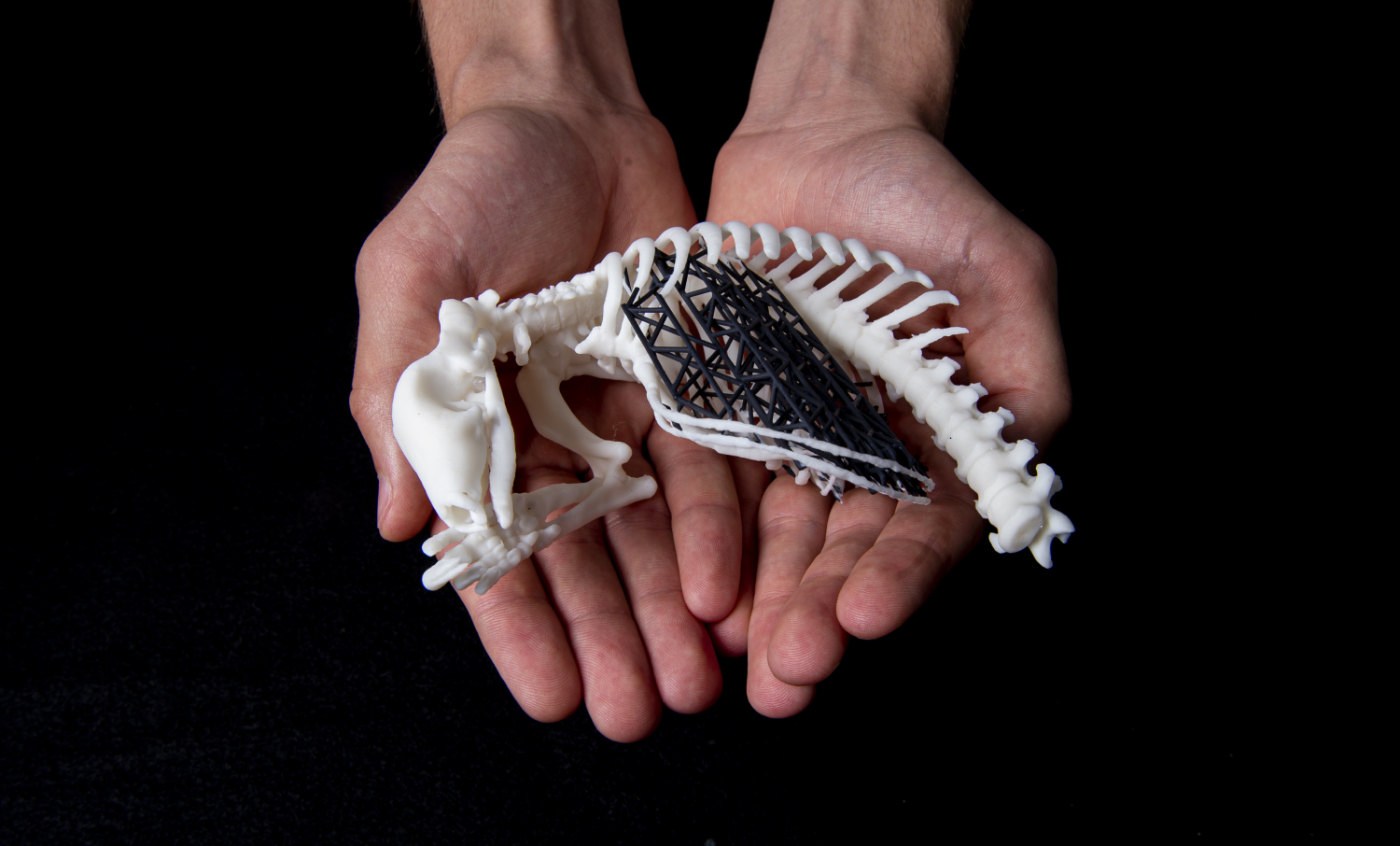

Verhulst set out to unravel the mystery of the pangolin tongue. He began by creating a digital rendering of the skeleton using a micro CT scan and 3D illustration software. From there, he could distinguish between the different structural elements of the animal’s anatomy and form hypotheses about pangolin-tongue propulsion.

“Pangolins have two rods around the tongue called xiphisternal bones that go all the way down,” Verhulst says. “Do they just guide it down into the abdomen, or can they curl and unfurl it to make the tongue extend and retract? I always use the word remarkable, because it really is.”

So impressive was Verhulst’s anatomical visualization of the pangolin that he was invited in April 2019 to the Experimental Biology Conference in Orlando where he presented to the American Association of Anatomists.

And the pangolin itself is enjoying a moment in the sun, albeit a tragic one. Verhulst and Holliday’s work is featured online for the June 2019 animal exploitation-themed issue of National Geographic. The creature also has its own documentary: The World’s Most Wanted Animal, available to stream on Netflix.

“I started out knowing nothing about them, and by this February I was telling everyone about World Pangolin Day,” says Verhulst, who is on track for med school. “It’s sort of an uncharted animal, and this research is really great to have on my résumé.”

As unusual as the pangolin might seem, this type of interdisciplinary endeavor is an everyday occurrence at the University of Missouri.

“This all came about because of the symposium at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, where the vet students put me, a bird-head anatomist, in the same room as a pangolin reproductive endocrinologist,” Holliday says. “That illustrates the collaborative nature of Mizzou right there.”